130 Years After Roanoke's First Lynching, Community Begins To Acknowledge City's Violent Past

Few places in Virginia have gone through the process of acknowledging their lynchings through the Equal Justice Initiative.

Less than a decade after Roanoke became a city, a white mob lynched William Lavender, a Black man accused of assaulting a white girl.

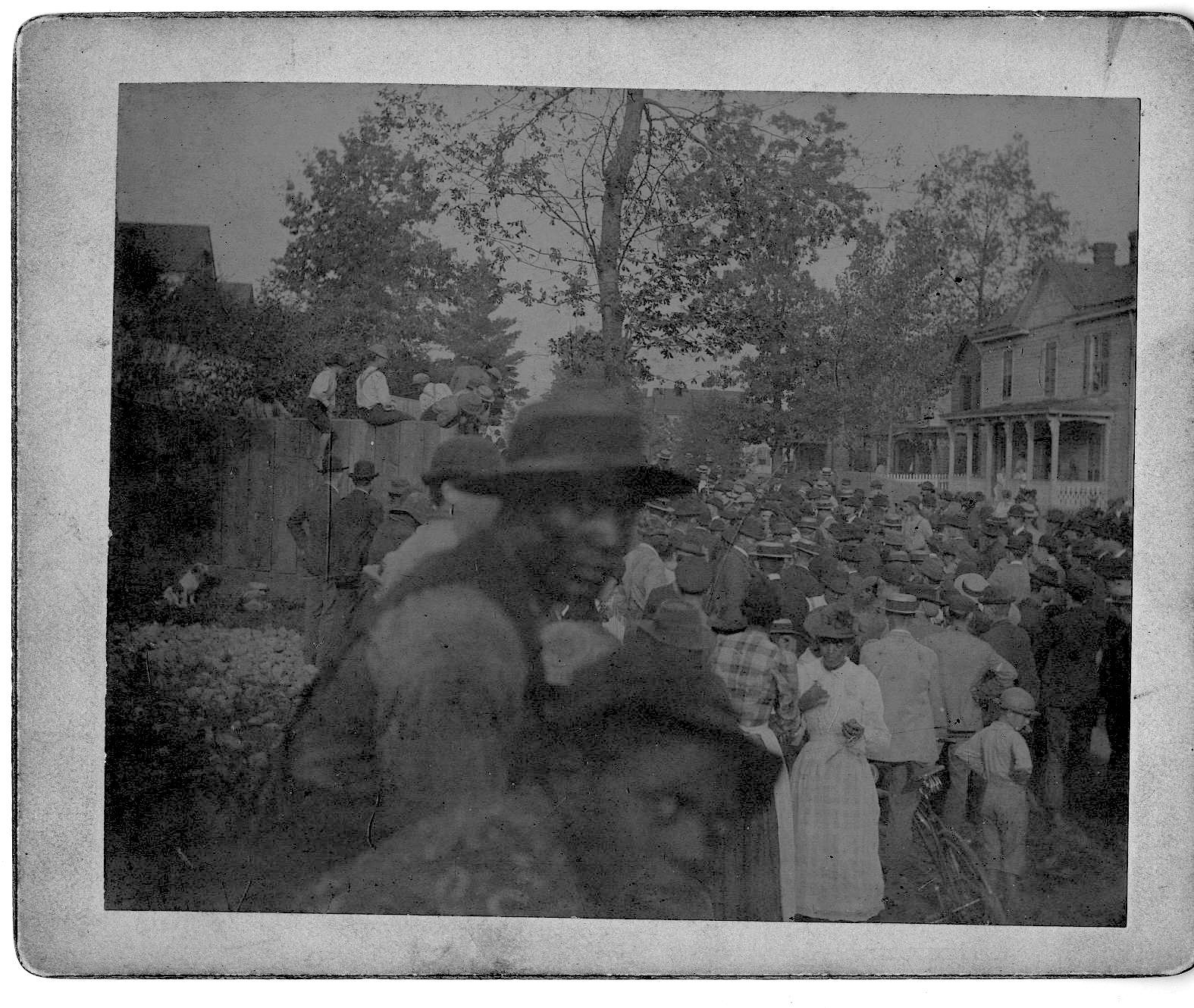

A year later, a city militia killed eight people when a mob tried to overpower the city jail. That’s where Thomas Smith, a Black man suspected of beating and robbing a white woman, was being held. Eventually, the mob abducted Smith and on the morning of Sept. 21, 1893, Smith’s killers hanged him from a hickory tree, riddled his body with bullets and burned his corpse on the banks of the Roanoke River.

This month, 130 years after the city’s first lynching, Roanoke is beginning to acknowledge this violent past.

A group of racial justice advocates will erect historical markers at the sites where Lavender and Smith were hanged. An unveiling of a marker where Smith was lynched — at Franklin Road and Mountain Avenue — is planned for Wednesday, Sept. 21 at a time to be determined.

A presentation on the history of Roanoke’s lynchings will be held at 6 p.m. on Thursday, Sept. 8 at the Claude Moore Education Complex (109 North Henry Street).

The events mark a years-long effort from locals working with the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit law firm that runs the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, known as the National Lynching Memorial, in Montgomery, Alabama. The memorial is dedicated to more than 4,400 victims of racial terror.

Few places in Virginia have gone through the process of acknowledging their lynchings through the Equal Justice Initiative, with Roanoke becoming perhaps the second locality to do so.

Charlottesville in 2019 erected a blue marker through EJI and remains the only Virginia city or county on an online EJI list last updated in June. Nationwide, 67 localities have erected historical markers, according to the site.

The process to get a marker is, in many ways, more complex than the process to erect gray state historic markers, 16 of which are sprinkled throughout Roanoke. Applicants must demonstrate the community’s commitment to racial justice work, testify they have read EJI’s lengthy reports on lynchings and Reconstruction and sign a pledge of EJI values.

Brenda Hale, president of the Roanoke branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), serves as chair of the Roanoke EJI Community Remembrance Project, which is made up of about 30 local groups.

“As a nurse, if you have an open, gaping wound and you don't treat it, it will get worse and worse, it can poison your bloodstream, and you can be septic and die,” Hale said. “So we want to prevent that from happening, heal the wound. Heal it.”

The history

Near dusk on Feb. 9, 1892, a 12-year-old white girl named Alice Perry ran home from the city market claiming that a Black man had accosted her on the street.

Police identified a suspect as Allen Stevens who was wearing rubber boots. But The Roanoke Times newspaper reported at the time that any Black man “who had on rubber boots was shadowed,” and Perry’s uncle arrested Lavender, who was wearing rubber boots.

Lavender was 19 and was raised in Blacksburg, according to a newspaper account of the time.

A mob of about 300 seized Lavender from a policeman’s home, took him to the banks of the Roanoke River and hanged him from an oak tree.

The headline in The Roanoke Times the following day read: “Viewed By A Thousand People.”

In the morning, Black residents on their way to work paused at the site near the Wasena Bridge “and gazed in horror at the awful spectacle,” the newspaper reported.

“Opinions in regard to the lynching were freely expressed all around town yesterday,” the newspaper article says. “It was the general feeling that a good thing had been done. Justice had been meted out in just deserts, and the dignity of the people maintained.”

A year later, a Botetourt County farmer’s wife identified in the historical record as “Mrs. Henry Bishop” came to Roanoke to sell produce. A Black man asked to buy wild grapes. As she got change, he beat her and stole her purse, which contained $1.93.

The account comes from “Like An Evil Wind: The Roanoke Riot of 1893 and the Lynching of Thomas Smith,” a 1992 article published in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography by Ann Field Alexander, a professor at what was then called Mary Baldwin College.

A detective arrested Smith, a married man in his 20s from Vinton who had recently lost employment at the Crozer Iron Company.

By the evening of Sept. 20, 1893, a large crowd had gathered outside the city jail. At some point, a militia called up to protect the prisoner fired upon the mob, killing eight people. The mayor, standing in the doorway of the jail, was shot in the foot and carried away. He would later go into hiding as members of the mob blamed him for the violence.

While authorities had slipped Smith out of the jail, they brought him back at about 3 a.m. and encountered about a dozen white men. “The police turned him over without a struggle; probably there was collusion,” Alexander writes. “Locating a hickory tree on Mountain Avenue with a low but sturdy branch, the lynchers tied a noose around Smith’s neck and hanged him.” Then they shot his body.

A man offered bits of the rope and tree to the crowd as souvenirs. Lynchers built a pyre of brush, doused Smith’s body with oil and lit it on fire along the river’s banks.

Alexander writes, “Among the estimated 4,000 spectators was Smith’s fifteen-year-old sister, who viewed the human bonfire from a distance.”

The next spring, the hickory tree failed to sprout new leaves. The legend spread that its death was a rebuke from Heaven.

In 1916, The Crisis, the NAACP magazine, published a brief account of an unidentified city official who said police had arrested a more likely suspect in the robbery earlier in the day and released him on the condition he leave Roanoke.

The legacy

Efforts to remember Roanoke’s lynchings came together at a lunch about three years ago between Brenda Hale and Councilman Bill Bestpitch at the now-defunct Carlos Brazilian restaurant.

Residents had visited the lynching memorial in Alabama and wondered why the city didn’t have any commemoration of the murders.

“I think we just have to come to grips with the fact that the lingering aftereffects of all of those things are still with us,” Bestpitch said. “And our job is not to try to blame anybody that's around today or trying to make anybody feel guilty about something that happened, you know, more than 100 years ago. Our job is to figure out how do we get past all of that and make sure that everybody feels like they're just as valuable as a member of our community, just as valuable as a citizen of the United States, as anybody else. And that's why I think this is important.”

Bestpitch emphasized the efforts are not a city initiative but community-led.

The coalition of groups spent months gathering information about the work Roanoke has done to confront parts of its racist history. That includes Black history tours, church activities, book groups and dialogues among people of different races.

Members also read about the history of lynchings, which were often public spectacles, attended by children and people having picnics.

“That was shocking to me that people could be that grotesque and callous and mean,” said coalition member Jennie Waering, a retired federal prosecutor. “I guess just the inhumanity of man to man was smack in my face.”

Turnover in EJI staff slowed the application process down a bit, coalition members said. But by this spring, members heard word that its 38-page proposal was approved. EJI provides and pays for the blue historical markers.

The plan is to erect a marker for Lavender — likely around the site of the Ramada Inn on Franklin Road that is being torn down — next February or the February afterward.

As part of the remembrance, residents will collect soil from the sites of the lynchings.

That will be placed in glass jars, some of which will live at the memorial in Montgomery, others of which will stay in Roanoke. Bestpitch said tentative plans are to house soil at the Harrison Museum of African American Culture and at the History Museum of Western Virginia.

In their application to EJI, coalition members noted that they “must be prepared to deal with some opposition, which we anticipate being minimal.”

Amy Christine Hodge, pastor of Mt. Zion AME Church and vice chair of the coalition, alluded to such a response when she read comments to a Roanoke Times story about the markers.

“I was surprised at the ignorance of our community: ‘Well, that happened. Why don’t you forget about it?’ ‘Why are they digging up the past?’ and all of that,” Hodge said. “We must remember, unless we forget and return to our old ways. We must remember. That's why we're doing this.”