Decades After Urban Renewal Razed Black Neighborhoods, Roanoke Prepares To Apologize

The apology is “intended to be an action document with firm commitments and identifiable results."

When Elvis came to Roanoke in 1972, cars would have wrapped around Kathleen Ross’s home during the sold-out show.

Ross was among a few residents who refused to move when the city took land for a new civic center. So the city built the center’s parking lot around her house.

“I told them that I would be willing to sell it if they would give me a decent price," Ross, who died in 2001, told a Roanoke Times reporter in the 1990s, years after she moved.

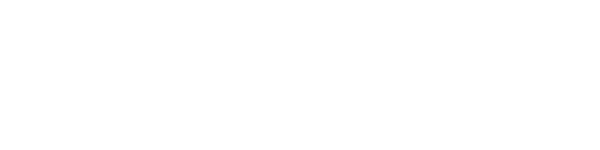

Now, almost 70 years after Roanoke began the process of urban renewal — which would go on to destroy 1,600 homes, shutter 200 Black-owned businesses, demolish two dozen churches and dig up nearly 1,000 graves to make way for the construction of Interstate 581, the civic center and post office — the city is preparing to apologize.

The city’s Equity and Empowerment Advisory Board, which is made up of seven citizen volunteers, has been crafting a public apology it hopes Roanoke leaders will issue by the spring or summer, according to Angela Penn, who chairs the board.

Roanoke is hardly alone in trying to atone for 20th-century infrastructure projects that demolished Black neighborhoods. In recent years, cities including Cincinnati, Knoxville and Charlottesville have issued apologies for their role in paving over communities.

To this day, urban renewal’s specter often haunts public policy conversations in Roanoke — from the future of the Gainsboro neighborhood to the prospect of development at Evans Spring.

Penn recalled how Roanoke residents invoked the pain of urban renewal during a community meeting at the Gainsboro library years ago when the city was drafting its master plan.

“One of the things that kept coming up, a recurring theme, was that there was no acknowledgement of what happened within the African American community, particularly with property, the way it was taken for public use.” Penn said during a July meeting of the EEAB.

Vice Mayor Joe Cobb said efforts began in 2019, when he, City Manager Bob Cowell, former assistant city manager Sherman Stovall and former Councilman Bill Bestpitch met with a dozen residents who lived through urban renewal.

(In recent days, some of those residents told The Rambler they were unavailable for interviews.)

“We learned, very quickly, two things,” Cobb said at the July board meeting. “One was we don't want an apology without action; there needs to be tangible steps connected with that. And that we need to work on some of that action.”

The apology is “intended to be an action document with firm commitments and identifiable results, not just apology language” and “will include financial commitments,” according to September meeting minutes from the Equity and Empowerment Advisory Board.

Penn said in an interview Tuesday that EEAB members are still working on exactly what form the actions or financial commitments might take.

During urban renewal, “many African-American families and businesses were forced to relocate from long established communities with no clear path to economic prosperity in Roanoke,” states a draft apology resolution, which the city released in response to a public records request.

The draft would ask City Council to extend “sincere apologies and regret for the pain and loss to the current and former residents of the City’s Urban Renewal districts for the actions of our predecessors in carrying out an Urban Renewal program,” and commit to “work towards better outcomes moving forward.”

Last month, members had a “robust conversation” about the draft and its wording, including whether it should take the form of a traditional resolution with its series of “whereas” clauses.

“This is still a work in progress,” Penn said. In the coming months, the board will seek perspectives from community members, including those who lived through urban renewal, before a final draft is released.

“We don't want this to be just the process where there was no involvement,” Penn said. “We want to make sure that what we recommend is good and solid and that we get it right.”

Jordan Bell, a community activist who has studied Roanoke’s history of urban renewal, said the city owes reparations to those who lived in the affected areas.

“The only way that this apology is going to be received by the community as a legitimate apology is if there's actual action items that follows the apology, and I'm not talking about 10 years from now,” Bell said.

He said he personally wants to see the city help revive the former Claytor Clinic property, which was one of the first Black-owned health clinics in Southwest Virginia. The city intended to use $5 million in federal pandemic funds for a healthcare hub in Gainsboro, but those plans fizzled. The city will instead do roadway and outdoor recreation improvements in the neighborhood.

“If I apologize for something that I did to my fiancée, after the apology I may go buy her some flowers,” Bell said. “Okay, you apologize, and the flowers are you renovating the Claytor property. You apologize, and the flowers are you building a playground in Gainsboro.”

Some residents who met with city leaders also want new ownership of the Dumas Center, once a community hub and hotel that hosted the likes of Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong.

“I’ll just be candid with you all, one of the sticking points was the Dumas Hotel,” Cobb told the EEAB. “This group of elders wanted to see the Dumas returned. They wanted to see something different with it. And that's just never been a reality.”

The building is owned by the nonprofit Total Action for Progress, which restored the dilapidated hotel in the 1990s at the urging of then-Mayor Noel C. Taylor, Annette Lewis, president and CEO of TAP, said in an email.

In 2018, Dumas Hotel Legacy, Inc., a group of community activists and business leaders, offered to buy the property when TAP put it on the market. Lewis said the group failed to meet purchase agreement conditions, leading to a breakdown in the sale. A judge later dismissed a lawsuit brought by Dumas Hotel Legacy against TAP.

TAP took the property off the market because several of the nonprofit's programs needed to relocate there, Lewis said. She described the building as well used today, with all office spaces fully occupied.

“TAP is grateful to have been chosen to renovate the historic building and keep it preserved for our Gainsboro community,” Lewis wrote. “We are pleased to provide valuable services for the community members and we welcome volunteers as well as ideas on how we can better serve our community.”

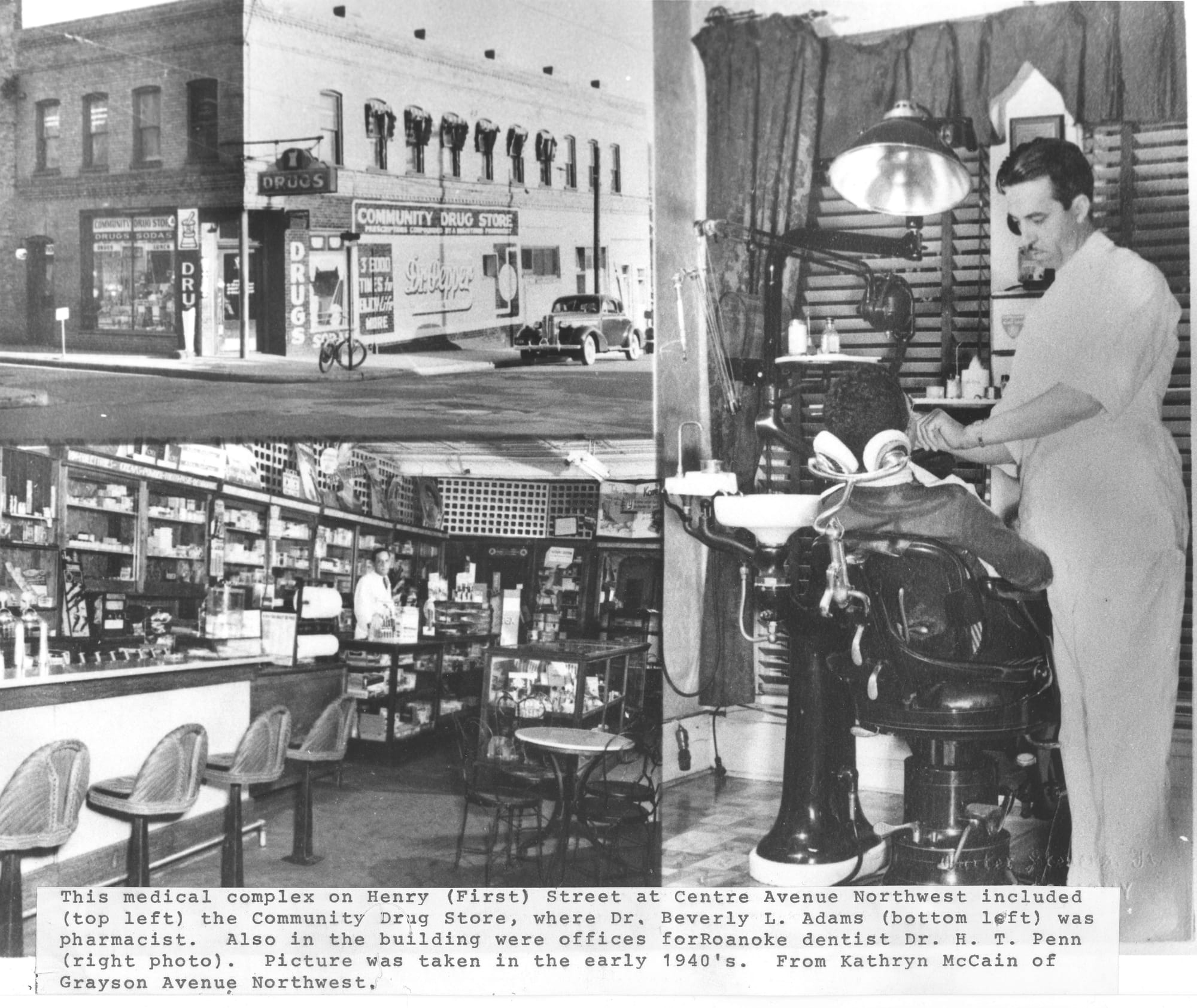

For some residents, the Dumas still serves as a symbol of the once-thriving Henry Street, known as Roanoke’s “Black Wall Street” before urban renewal, Bestpitch recalled in an interview last week.

This photo from 1979 was part of the Roanoke Redevelopment and Housing Authority's documentation of areas in Roanoke before, during, and after various redevelopment projects. The view of Henry Street in Gainsboro shows the former Dumas Hotel, at left, and Palace Hotel, at right, well after urban renewal hollowed out the area. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE VIRGINIA ROOM AT THE ROANOKE PUBLIC LIBRARIES

“To me, the pain in the room whenever we got together with them was palpable,” he said. “It was just so clear that many of those people are still carrying around such hurt and such pain from what happened that it’s hard to move forward beyond that to anything else.”

At the time, white city leaders saw razing neighborhoods — which they saw as blighted — for the interstate and civic center as a positive step for Roanoke, Cobb told the EEAB.

“They truly believed that this was a way to bring progress,” Cobb said, “and weren't thinking so much about the redlining and historically what the interstates coming through were doing, where they were being directed, and what the repercussions of that would be.”